Developing metacognition in your school

Developing thinking

Central to metacognition is thinking about thinking. For example, getting pupils to consider how they think, the tools they use for thinking and how they could improve their thinking. Thinking includes elements such as, how people think through a problem, the thought processes people engage with when making a decision, the thinking people use when tackling writing an essay, the thought processes involved in revision. Teachers can support pupils to develop a repertoire of thinking tools and techniques. All of us need help when it comes to thinking, whether it is for breadth, depth or consideration for different viewpoints. Teachers can help pupils to develop particular strands of thinking, e.g. analytical thinking, evaluative thinking, scientific thinking.

Thinking maps

Thinking maps are one set of tools that can help pupils achieve greater breadth or depth of thinking.

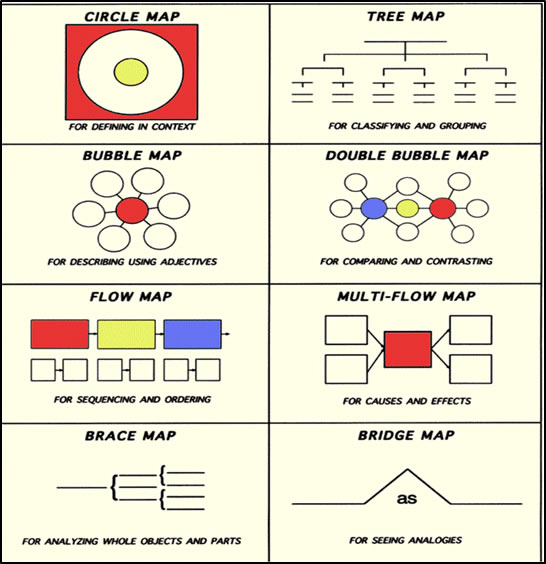

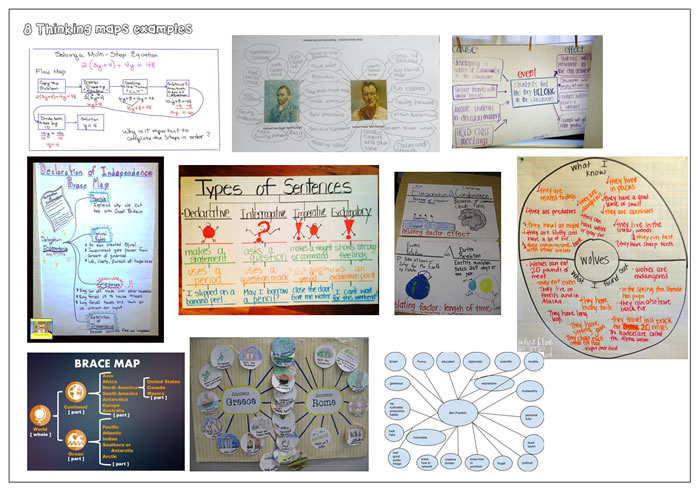

In ‘Student successes with thinking maps’ by David N. Hyerle and Larry Alper (2nd Edition), 8 thinking maps are described (as seen below).

- Thinking maps should not be taught in isolation, but should be selected to meet the needs of particular task within a topic.

- Discussion should take place as to why this thinking map is appropriate for the task (whilst also drawing pupils’ attention to other strategies that could be used).

- It is important to explicitly teach this as a ‘strategy for learning’ and evaluate its usefulness at the end.

Thinking maps support pupils to think by getting more breadth and/or detail into their thinking than may otherwise be achieved. For many lower ability and disadvantaged pupils having the right language is a barrier to achieving success. “Thinking maps can offer an approach which helps more focused language to develop. Maps allow for interactions between listening, speaking, reading and writing within a language of thinking that bridges visual-spatial and verbal representations. Consequently, they profoundly change both the language used within the classroom and the language demands of the classroom. This change allows students who struggle with listening, speaking, reading, or writing, or who previously could only stand on the side-lines, to get into the game.” (Hyerle & Alper).

Thinking maps can change the way teachers talk to pupils and the way pupils talk to themselves and each other. Pupils can he heard using words such as ‘think, clarify, sequence, analogy, and brainstorm’.

For example:

"Nick, a Year 6 pupil with a learning disability shared a Double Bubble Map he made to compare and contrast the main characters in two books he read during independent reading time. He not only read the words and phrases on his map to his classmates; he also elaborated upon each idea by offering details and examples from the two books he read. For example, when discussing the similarities of the characters regarding the making of new friends, Nick explained that Robinson met a native person on his island, while Cody met a person in the woods. Both found new friends to help them survive while they were stranded in isolated environments, Robinson on an island and Cody in the arctic forest of Alaska. Nick recalled key facts about each character, and what is more impressive is that making the map help him to remember, integrate, and understand the books at a deep level. Talking from the map allowed him to share what he knew in nicely organised and coherent discourse. Nick notes that he never would have remembered all those details if he hadn’t constructed that kind of map. He went on to explain that the Double Bubble and Tree maps help him more than other Thinking Maps because they specify ways of thinking he previously found difficult." (Extract from Hyerle and Alper).

It is important that pupils learn not only to use the maps but to evaluate their use of them. This helps them to see this as a strategy that they can apply to different types of activity and learning challenges.

Thinking maps help pupils to reflect on their own thinking: thus engaging in metacognition. They support internal dialogue whilst a pupil is working on 'thinking' and helps to mediate thinking between individuals in the classroom. Not only do the maps foster pupils’ increased awareness of their individual cognitive and metacognitive style, but they allow the teacher to glimpse pupils’ metacognition, thus enabling them to assess areas of strength and weaknesses to support accelerated learning.

In addition to thinking maps, other tools can be used to help pupils to think in greater breadth or detail, help them connect learning, organise their thoughts and share their ideas with others.

For example:

- Brainstorming

- Mind mapping

- Post it note activities

- Logo visual thinking

- Techniques such as What Went Well and Even Better If

- Questioning each other

- Putting statements on a scale of 0-10

- Diamond 9 ranking

- PMI - Plus, Minus, Interesting

- CAP - Consider all points

- PCQ - Pros, Cons, Questions

- Fishbowl activities

- Categorising : such as Venn diagrams

- De Bono's 6 thinking hats

Thinking maps are a great way to get more breadth and depth into writing. E.g. Brainstorming words associated with a topic helps the brain to recall information from long term storage and results in longer, more detailed essay writing than would otherwise be the case. Collaborative creation of maps is a good way to support pupil to think before engaging in an independent writing task.

Like to share?

Why not send us your resources.